Introduction:

Nestled along tropical and subtropical coastlines lies a unique ecosystem where land meets the sea – the mangrove forest.

Mangroves are a group of remarkable trees and shrubs that have developed incredible adaptations to thrive in the harsh intertidal zone, where salt and fresh water ebb and flow with the whims of the tides.

While often unappreciated, these forests serve as vital guardians of the coasts, protecting millions of people and their livelihoods.

What are Mangroves?

Mangroves aren’t a single species but rather a diverse group of trees and shrubs specifically adapted to thrive in a harsh environment – the intertidal zone. This means they occupy coastal areas where saltwater and freshwater mix, constantly battling fluctuating tides, muddy soils, and intense salt levels.

Special Adaptations of the Mangroves:

● Salt Management:

- Some mangroves excrete salt through their leaves.

- Others have special filters in their roots to block salt from entering.

● "Breathing" Roots:

Mangroves overcome the problem of soggy, oxygen-poor soil through specialized root systems.

- Prop Roots: Tangled, arching roots above the mud provide stability and air access.

- Pneumatophores: Pencil-like root projections sticking straight up from the ground, like little snorkels for the roots.

● Seed Dispersal:

Mangrove seeds are buoyant and can float with the tides. They often start germinating while still on the parent tree, developing into ready-to-plant “propagules.”

● Viviparous germination:

Vivipary (literally, “live birth”) is a type of seed germination where the seed begins to sprout while still attached to the parent plant. This adaptation is common in mangrove environments to give seedlings a head start in harsh conditions.

Global Distribution of the Mangroves:

Tropical and Subtropical Coastlines: Mangroves primarily thrive in warm climates between 30° North and 30° South latitudes. They cannot tolerate freezing temperatures.

Coastline Specifics: Mangroves favor:

- Sheltered bays and estuaries

- River deltas

- Tidal flats

- Lagoons

Major Mangrove Regions:

Southeast Asia: It holds the largest and most diverse mangrove forests. Indonesia has the most extensive mangrove coverage globally.

South and Central America: Brazil, Mexico, and other countries boast significant mangrove areas.

Africa: Mangrove forests are found along the eastern and western coastlines of the continent.

Australia and South Pacific Islands: Mangroves dot suitable coastlines throughout the region.

Factors Influencing the Growth of the Mangroves:

Temperature:

Consistent warmth is vital for mangrove survival. Like all plants, mangroves rely on photosynthesis and other chemical processes to grow and thrive.

These processes are temperature-dependent, working best within a specific warmth range. While precise temperature tolerances vary among mangrove species, most thrive in average temperatures of 20°C (68°F) or higher.

Mangroves are extremely sensitive to freezing temperatures. Frost can cause cell damage and death within the trees, limiting their distribution to tropical and subtropical climates.

Salinity:

Mangroves tolerate a wide range of salinity, from brackish water (fresh and saltwater mix) to full-strength seawater.

Saltwater Survival: Mangroves have incredible adaptations that allow them to deal with high salt levels that would kill most plants.

These adaptations include:

- Salt Exclusion: Some mangroves have specialized filters in their roots that prevent most salt from entering the plant.

- Salt Excretion: Others excrete excess salt through glands in their leaves.

- Salt Storage: Certain species concentrate the salt in older leaves or bark, which are shed.

Brackish Tolerance: Many mangroves flourish in brackish water, where rivers meet the sea, and salinity levels can change significantly depending on tides and rainfall.

Tidal Fluctuations:

The trees are adapted to regular inundation and exposure due to tides. Mangroves have evolved unique root systems to cope with periodic flooding and retreating tides. Prop roots and pneumatophores allow them to “breathe” air even when the soil is waterlogged.

Tides play a vital role in distributing mangrove propagules. Also, the movement of tides brings in nutrients and removes waste products, supporting the complex food webs within mangrove ecosystems.

Soft Sediments:

The network of roots helps trap sediment, preventing erosion and building up the coastline over time. Mangroves need muddy, oxygen-poor soils to anchor their unique root systems.

Prop roots spread widely and intertwine, providing a stable foundation in unstable soil. Meanwhile, pneumatophores and other root systems delve into the oxygen-poor mud, drawing up nutrients and water.

Mangroves - the Natural Buffer Against Storms and Erosion:

Mangrove forests stand as nature’s shock absorbers. Their intricate network of roots and dense foliage forms a formidable barrier against storm surges, waves, and even tsunamis.

These root systems act like a mesh, dissipating the energy of incoming waves while simultaneously trapping sediments.

By doing so, mangroves dramatically reduce coastal erosion and safeguard homes and vital infrastructure from the damaging power of the sea.

Wave Attenuation:

The complex network of prop roots, pneumatophores, and submerged roots act like a natural barrier, slowing down incoming waves and reducing their energy.

The rough surfaces of trunks, branches, and roots create friction, further dissipating wave energy and reducing the distance waves can effectively travel.

Storm Surge Reduction:

By breaking up incoming waves, mangroves lessen the force and height of storm surges, minimizing the damaging impact on inland areas.

Mangroves thrive in the shallow intertidal zone, where water depth further helps reduce waves and storm surge power.

Erosion Control:

Mangrove roots effectively trap and hold sediments brought in by tides and currents. This helps stabilize shorelines and prevents erosion.

Leaves, propagules, and other organic material from mangroves decompose, contributing to soil buildup and counteracting erosion.

In some cases, mangroves can facilitate land expansion by trapping sediments and encouraging additional growth, further protecting the coast from the sea’s force.

Other Benefits:

Windbreak: Dense mangrove forests can reduce wind speeds during storms, further protecting coastal communities.

Tsunami Defense: While not a foolproof barrier, some studies suggest that healthy mangrove forests can help reduce the impact of tsunamis.

Water Filtration and Quality: Mangrove roots and sediments trap pollutants and filter runoff before it reaches the open ocean, maintaining healthy coastal ecosystems.

Mangroves - Nurseries of the Sea:

Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation: Mangroves rank among the most carbon-rich ecosystems on the planet. They store substantial amounts of “blue carbon” in their roots, sediment, and biomass, helping to combat climate change.

Biodiversity Powerhouse: Mangrove forests provide vital habitat, nursery grounds, and breeding areas for an immense array of wildlife:

- Fish, crabs, shrimp, and other commercially important species

- Diverse bird populations, including wading birds, egrets, and herons

- Reptiles like crocodiles and snakes

- Mammals such as monkeys or even tigers in some regions

Sustainable Livelihoods for Local Communities: Mangroves support vital coastal economies through:

- Fisheries and aquaculture

- Ecotourism opportunities

- Sources of wood and other forest products, when responsibly managed

Mangroves - Under Threat:

Sadly, despite their immense ecological and economic value, mangrove forests are among the most threatened ecosystems on Earth. Studies show that mangrove loss rates have been higher in some regions than in tropical rainforests.

Coastal development, pollution, and aquaculture have taken a tremendous toll. Losing this precious natural armor against climate change and rising sea levels could have devastating consequences.

Coastal Development:

- Clearing for urbanization, aquaculture ponds, tourism resorts, and other infrastructure directly destroy and fragment mangrove forests.

- Development alters natural water flow and tidal patterns, which mangroves depend on.

Pollution:

- Agricultural runoff carries pesticides and fertilizers, harming mangroves and reducing water quality.

- Industrial waste and sewage can contain heavy metals and other toxins detrimental to the ecosystem.

- Oil spills pose a significant threat, smothering trees and affecting marine life within mangroves.

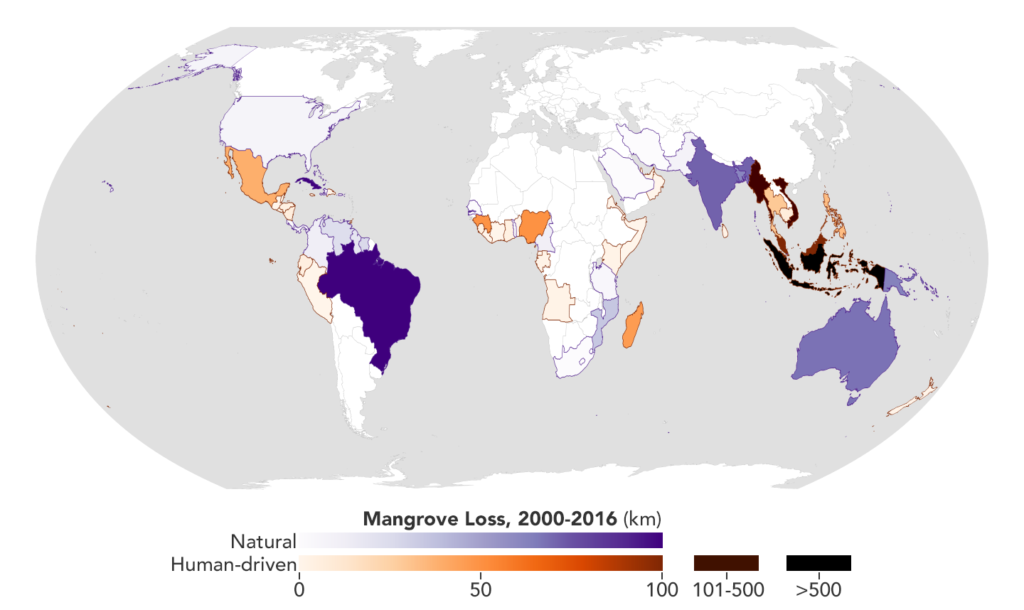

This map shows the location and severity of mangrove habitat loss, measured in kilometers, caused by natural and human drivers from 2000 to 2016. Darker areas experienced more loss in the period.

Overexploitation of Resources:

- Unsustainable cutting for firewood, timber, and charcoal production degrades mangrove forests.

- Overfishing and unsustainable harvesting of mollusks, crabs, and shrimp disrupt the food web.

Climate Change:

- Rising sea levels threaten to inundate mangroves, especially those with limited ability to move inland.

- Changes in rainfall patterns can alter salinity levels and stress the trees.

- Increasing extreme storms can cause physical damage and erosion.

Invasive Species:

Introduced plants and animals can outcompete native mangroves and disrupt the delicate ecological balance.

Lack of Awareness and Management:

Understanding the mangrove’s critical role can lead to better management decisions and under-prioritization of protection.

Mangroves - Restoration and Revival:

Restoring mangroves often requires working beyond the trees themselves. Address threats in the broader watershed and promote sustainable coastal management practices. Successful restoration depends heavily on the support and involvement of local communities that rely on mangroves.

Identify the problem: Before action, it’s crucial to pinpoint the cause of mangrove loss or damage. Is it pollution, coastal development, altered water flow, or another issue?

Prioritize actions: Once the source is understood, you can strategize the most appropriate restoration approaches.

Promote natural water flow: This is essential for healthy mangroves. Actions may include removing blockages, re-establishing tidal channels, or dismantling dikes that disrupt natural flow.

Address pollution: Depending on the situation, this can involve working with industries or agricultural sectors to reduce pollutant discharge or establishing buffer zones to filter runoff.

Species selection: Choose mangrove species that are native to the area and best suited for the specific conditions of the restoration site.

Nursery cultivation: Seedlings may need to be raised in a nursery before outplanting, especially if natural regeneration is limited.

Community involvement: Engaging local communities in planting increases success and long-term stewardship.

Create protected areas: Establishing mangrove forests as marine protected areas or reserves aids long-term conservation.

Promote sustainable practices: Work with communities on sustainable harvesting, alternative livelihoods, and minimizing future impacts.

Education & Awareness: Raise public awareness of the value of mangroves to encourage conservation and reduce behaviors that harm them.

Track progress: Regularly monitor the health of the replanted mangroves and the surrounding ecosystem.

Adapt as needed: Restoration is not a one-time fix. Adjust methods based on monitoring results and observed challenges.

Mangroves - Call to Action:

Mangroves are far more than muddy swamps. They are resilient fighters protecting both people and nature from the relentless forces of the ocean. Understanding their importance, curbing harmful practices, and backing restoration efforts are critical to ensure these coastal guardians can continue shielding our shores for generations.

It’s time to recognize that our planet’s health and countless communities’ well-being depend on the survival of these remarkable “walls of the coast.”

Projects for the Protection of the Mangroves:

Various projects run in different parts of the world with the same aim and objective – to protect and conserve the Mangroves – the walls of the coastal regions.

Large-Scale Initiatives:

Global Mangrove Alliance: A collaboration between significant conservation organizations (WWF, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, Wetlands International, IUCN) aiming to increase mangrove coverage by 20% by 2030. They focus on restoration, advocacy, and knowledge-sharing.

Blue Forests Project: Led by The Nature Conservancy, this project assesses the carbon storage potential of mangroves and develops blue carbon financing mechanisms to support protection and restoration.

International Blue Carbon Initiative: A coordinated effort, including The Ocean Foundation, focused on mitigating climate change through the restoration and sustainable use of coastal and marine ecosystems. Mangroves are a vital part of their work.

Region-Specific Projects:

Gazi Bay Mangrove Restoration (Kenya): A community-led project with successful replanting efforts, demonstrating the link between mangrove health and improved fisheries.

Mangrove Action Project (MAP): Works in multiple countries throughout Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and other regions on restoration, education, and sustainable mangrove use.

Community-based Ecological Mangrove Restoration (CBEMR): A widely implemented restoration approach with a strong focus on local stakeholder participation in the Philippines and other areas facing mangrove loss.

Conclusion:

Mangroves, often dismissed as muddy swamps, are potent guardians of our coasts. Their loss translates to rising vulnerability for countless coastal communities and ecosystems. Protecting and restoring mangroves demands immediate focus and investment – an investment in the future health of our planet and ourselves.

It’s a choice for a safer, healthier, and more resilient future. It’s time to end the neglect. By understanding their invaluable role, stopping destructive practices, and backing restoration initiatives, we can ensure these coastal protectors continue to shield us for generations to come.