Introduction:

Imagine a world without soil. No lush forests, vibrant fields, or food-sustaining life as we know it. Soil isn’t just dirt beneath our feet – it’s the cornerstone of our planet’s ecosystems. Every handful teems with secrets, whispers of an extraordinary story – the soil formation process.

The soil formation process is a dance of geology, climate, and the tireless work of living things. It’s a testament to the interconnectedness of our world. Understanding this process offers insights into agriculture, environmental sustainability, and our planet’s dynamic history.

Let’s delve into this incredible transformation – where rocks crumble, organic matter intermingles, and the foundation for life takes shape.

Understanding the Building Blocks of Soil

What lies beneath our feet isn’t just dirt. It’s a life-giving tapestry of minerals, remnants of living things, and endless microscopic activity – the foundation known as soil. Understanding how soil forms help us appreciate its vital role in our world, and that journey begins with the essential ingredients.

Soil is a dynamic, natural body comprised of mineral and organic solids, gases, liquids, and living organisms. It has evolved over time, possesses distinct layers (horizons), and serves as a medium for plant growth, water filtration, and countless biological and environmental processes.

What is Soil Made Of?

Mineral Components

Soil begins with rock. Over time, forces like wind, water, and ice physically and chemically break down those rocks into tiny particles. These particles, primarily sand, silt, and clay, give soil its basic texture and determine its ability to hold water and nutrients.

Organic Matter

This is where it gets lively! Organic matter is the decomposed remains of plants and animals. It’s like nature’s slow cooker, continuously releasing nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus that feed growing plants. Organic matter also works wonders for soil structure, making it spongy and giving roots space to spread.

Soil isn’t just ingredients thrown together; it’s alive! Countless bacteria, fungi, and other organisms call soil home. These tiny powerhouses are the real stars of the soil formation process. They further break down organic matter, transform minerals, and help plants absorb nutrients.

Why Does it Matter?

Understanding the pieces that makeup soil shows us how this seemingly ordinary substance is at the heart of thriving ecosystems. Healthy soil means flourishing plants, which feed us and support a whole chain of life. It filters water, regulates our climate, and is the bedrock for many natural processes. The next time you dig in the garden or go for a hike, remember the ground you walk on isn’t just dirt – it’s a complex, living world in the making.

The Journey of SOIL FORMATION PROCESS

The transformation of solid rock into the fertile soil that sustains life is a testament to nature’s intricate processes. The soil formation process is a complex journey shaped by several key players.

Parent Rock: The Foundation

The story of every soil begins deep within the Earth itself. Parent rock, the bedrock from which soils arise, lays the groundwork for the complex tapestry of nutrients and textures that define soil fertility. Much like an artist’s canvas sets the stage for their vision, parent rock dictates the essential mineral composition upon which the soil formation process unfolds.

1. Types of Parent Rock and Their Influence:

Soil begins its journey with parent rock, the original mineral material. The type of parent rock significantly affects the soil’s properties. Common parent rocks include:

- Igneous Rocks: Formed by cooling magma or lava, they create mineral-rich soil.

- Sedimentary Rocks: Made of layered sediments, they often lead to diverse soil types.

- Metamorphic Rocks: Changed by heat and pressure, they offer a varied mineral composition.

2. Weathering: Breaking Down Bedrock

A. Physical Weathering: Mechanical processes break down the parent rock into smaller pieces:

- Freeze-thaw cycles: Water expands within rock cracks when frozen, eventually fracturing the rock.

- Temperature fluctuations: Rocks expand and contract with temperature changes, causing stress and weakening.

B. Chemical Weathering: Chemical reactions alter the rock’s composition:

- Oxidation: Minerals react with oxygen, such as when iron rusts.

- Hydrolysis: Water reacts with minerals, altering their structure.

The Role of Living Organisms

- Plant Life and Decomposition: By the process of biological weathering, plants extend roots into weathered rock, further breaking it down. Dead plants decompose, adding organic matter and nutrients, contributing to the soil formation process.

- Soil Microbes and Nutrient Cycling: Bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms break down organic matter, releasing essential nutrients back into the developing soil. They play a critical role in the soil formation process, driving nutrient availability and creating a rich ecosystem.

The intricate interplay between parent rock, weathering, and living organisms is the core of the soil formation process. Over time, these elements transform sterile rock into fertile soil, teeming with life and supporting many ecosystems.

Shaping the Soil: Climate and Time

Beyond the bedrock and bustling organisms, the dynamic forces of climate and the relentless passage of time dramatically sculpt the developing soil.

How Does Climate Affect Soil Formation?

Temperature and Weathering Rates:

- Warm temperatures accelerate chemical weathering, speeding up the breakdown of parent rocks and minerals.

- In contrast, cold climates slow down these reactions, hindering the soil formation process.

Precipitation and Leaching:

- In high-rainfall regions, water moves through the soil, leaching (dissolving and carrying away) nutrients and soluble minerals. This can lead to acidic soils with lower nutrient content.

- Arid climates experience less leaching, resulting in the potential buildup of salts and minerals within the soil profile.

Time: The Silent Contributor

The soil formation process is a journey, not a sprint. Over vast periods, the subtle but relentless forces of climate and weathering interact with other soil-forming factors. Overtime:

- Gradual weathering continues to break down rock fragments.

- Organic matter steadily accumulates from plant and animal residues.

- Young Soils: Newly formed soils closely reflect the parent material, often with coarse textures and limited organic content.

- Mature Soils: With time, soils develop distinct layers, richer organic content, and complex profiles that reflect the long-term influence of climate.

The Interplay of Climate and Time

Climate and time act in concert to shape soil characteristics:

- Tropical Climates: Warm temperatures and heavy rainfall promote rapid weathering and intense leaching, often creating deep, weathered soils that may lack nutrients.

- Temperate Climates: Moderate temperatures and rainfall create a balance, promoting soil development with a good mix of minerals and organic matter.

- Arid Climates: Limited weathering and leaching create younger soils, potentially higher in mineral salts.

It’s important to understand that the soil formation process is a continuous journey. Climate and time remain relentless sculptors, constantly refining and reshaping the soils that sustain life on our planet.

External Influences: Factors Affecting Soil Formation

While parent rock, weathering, and organisms form the core of the soil formation process, several external factors greatly influence how this process unfolds in different environments. Identifying how these factors shape soil development is key to understanding our planet’s vast diversity of soils.

Which of the Following Factors Does Not Affect Soil Formation?

Let’s examine some critical factors and why each of them plays a role in the soil formation process:

Topography (Slope and Drainage):

- Steep slopes: Increased erosion can move young soils away, limiting their development time.

- Low-lying areas: Waterlogging can slow decomposition and create poorly aerated soil conditions.

- Well-drained slopes: Promote a balance of moisture and oxygen availability, ideal for healthy soil development.

Organisms (Plants and Animals):

- Plant type and density: Influence organic matter input, root structures, and nutrient uptake.

- Burrowing animals: Mix soil layers, improve aeration, and break down organic matter.

- Microbial communities: Crucial for organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, key to the soil formation process.

Time:

- Time is a master sculptor in the soil formation process. Older soils typically exhibit more developed horizons and distinct layers.

- Young soils retain characteristics of the parent rock, reflecting shorter development periods.

Parent Material:

- This IS a core factor in the soil formation process. Parent rock’s mineral composition and weathering properties define the initial building blocks of the soil.

The “incorrect” factor in this list is Parent Material. It is a fundamental aspect of soil formation rather than a purely external one.

These factors interact on various scales, from localized variations in a landscape to broad regional patterns influenced by climate and vegetation zones. Understanding this dynamic interplay is essential for recognizing how soils support different ecosystems and how changes in a single factor can ripple through the entire soil formation process.

Notably absent from the list is climate, but it deserves special mention. Temperature and precipitation patterns profoundly shape weathering, organism activity, and soil leaching rates. This is why we find starkly different soils in deserts versus rainforests; climate exerts a powerful influence on the soil formation process.

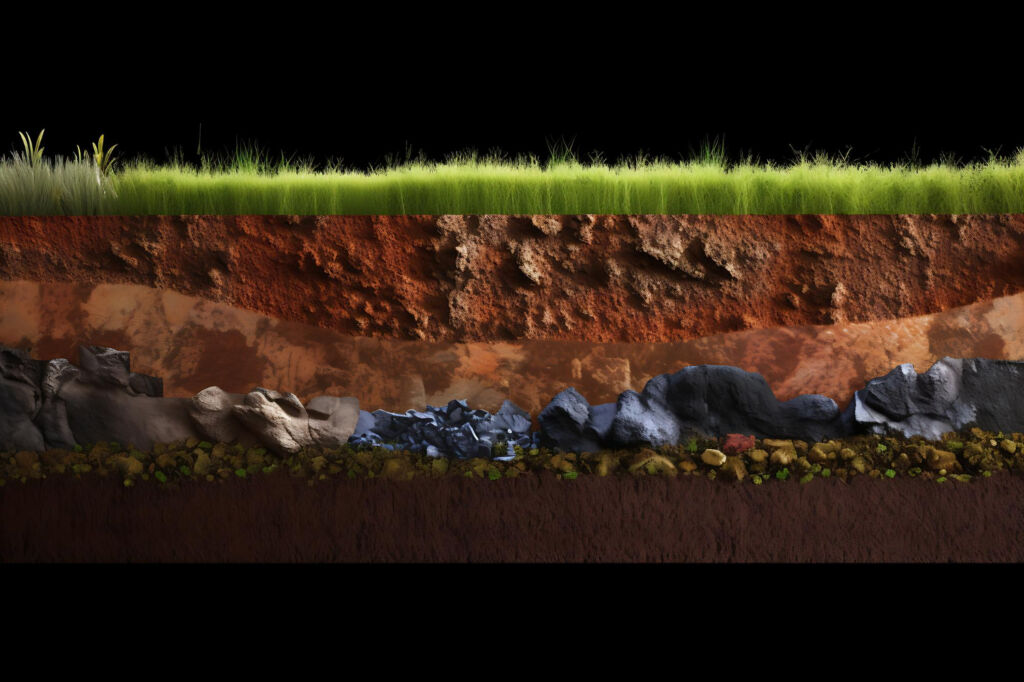

Layers of Complexity: Soil Horizons

Over time, the soil formation creates distinct layers known as soil horizons. These horizontal layers reveal a soil’s unique development story, reflecting the influence of climate, organisms, and the ongoing transformation of parent material.

Differentiating Soil Horizons

Soil scientists are like detectives of the natural world, carefully examining visual and tactile clues to unlock the secrets of soil formation and history. Here’s how they analyze those observable properties:

Color:

- Dark Colors: Typically signify high organic matter content, especially in the topsoil.

- Reddish or Yellowish Hues: Indicate the presence of oxidized iron compounds. The intensity of the color can indicate the degree of weathering and drainage in the soil.

- Gray or Bluish Tones: Suggest poor drainage and waterlogged conditions, limiting oxygen availability and affecting nutrient cycling.

- Mottled Patterns: Variations in color within a horizon can point to fluctuating water levels or the movement of specific minerals through the soil profile.

Texture:

- Sandy: Feels gritty, indicating larger rock particles. Sandy soils drain quickly but have limited nutrient-holding capacity.

- Silty: Smooth, somewhat powdery texture. Silt holds more water and nutrients than sand, making it more fertile.

- Clayey: Sticky and can be easily molded. Clay soils retain water well but can become compact and impede root growth.

- Loam: A combination of sand, silt, and clay, considered ideal for agriculture with a balance of drainage and nutrient retention.

Structure:

- Granular: Small, crumbly aggregates with good pore space for air and water movement.

- Blocky: Angular or cube-like structures can become compact with high clay content.

- Platy: Flat, plate-like structures that hinder water flow and root penetration.

- Prismatic & Columnar: Tall pillar-like structures often associated with specific environmental conditions or clay mineral content.

Presence of Roots and Organisms:

- Abundant Roots: Typically found in topsoil where nutrients and water are most plentiful.

- Root Channels: Left by decaying roots, improve water infiltration and aeration.

- Burrow Holes: Created by earthworms, insects, and larger animals, enhance soil structure and nutrient cycling.

Scientists carefully analyze these properties within a soil profile and piece together the dynamic soil formation process. Each horizon reflects the intricate dance between climate, parent material, biological activity, and the relentless passage of time.

O Horizon (Organic Layer)

- Primarily composed of decomposing organic matter like leaves, twigs, and other plant debris.

- Often dark in color due to the presence of humus, a partially decayed organic material.

- Supports a thriving population of microorganisms that aid in further decomposition and nutrient release

A Horizon (Topsoil)

- The uppermost mineral layer, where organic matter mixes with weathered rock.

- Most biologically active zones contain a high concentration of roots and soil organisms.

- Essential for plant growth, providing nutrients, water, and air.

B Horizon (Subsoil)

- There is less organic matter than the topsoil, with a higher accumulation of minerals like iron, aluminum, and clay leached from above.

- Often exhibits distinct coloration, such as reddish hues from oxidized iron compounds.

- It may contain denser layers that restrict water and root penetration

C Horizon (Weathered Parent Material)

- Consists of partially weathered parent rock, showing the transition from rock to soil.

- Limited biological activity compared to upper horizons.

- Provides the mineral foundation for the overlying horizons.

R Horizon (Bedrock)

Think of the R horizon as the Earth’s ancient canvas upon which the masterpiece of soil is slowly painted. It consists of:

- Solid, Unweathered Rock: This is the original parent material, untouched by the transformative processes of weathering.

- Types of bedrock: The bedrock’s composition varies greatly, including igneous rocks like granite, sedimentary rocks like limestone, or metamorphic rocks like gneiss. This initial composition lays the groundwork for what the soil will eventually become.

- The Depth Factor: The depth of bedrock can be highly variable. In some areas, it might be directly beneath the topsoil, while in others, several meters of weathered layers lie between the topsoil and the bedrock.

- Limitations: Bedrock presents a barrier to root penetration and water movement. However, cracks and fissures in the bedrock allow for some root growth and gradual weathering processes.

The presence of bedrock establishes the base of the soil profile. Over time, weathering and biological activity will gradually break down this solid rock, generating the ingredients for the diverse soil layers above.

The soil formation process is beautifully illustrated within the layered structure of a soil profile. Each horizon tells a chapter within the long and complex story of how lifeless rock transforms into the rich, fertile medium we call soil.

Importance of Soil

Soil is where life flourishes. Plants anchor their roots, drawing sustenance from their depths. Countless creatures burrow and thrive within it, forming intricate food webs. Soil filters water regulates our climate, and stores vast reservoirs of nutrients within its layers.

Fertile soils nourish plants, providing the basis for agriculture and our entire food supply chain. Healthy soils ensure the growth of nutrient-rich crops, ultimately supporting human health and well-being.

Soil teems with life, from microscopic bacteria and fungi to earthworms and burrowing animals. This rich biodiversity enhances soil structure, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience.

Soil is a natural filter that purifies rainwater and replenishes groundwater reserves. It also regulates water flow, mitigating floods and preserving water resources for human use.

Soils store vast amounts of carbon, playing a crucial role in mitigating the effects of climate change. Healthy soil practices promote carbon sequestration, removing excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Human Impact on Soil Formation

While natural forces like weathering and climate have shaped soil formation processes for eons, human activities have recently become increasingly powerful. Our footprint on the earth alters the natural landscape, influencing the rate and even the direction of the soil formation process.

Negative Impacts

- Accelerated Erosion: Deforestation, intensive agriculture, and overgrazing strip away protective vegetation, exposing soil to wind and rain. This leads to rapid topsoil loss and can leave behind less fertile layers.

- Compaction: Heavy machinery and excessive foot traffic compress soil, reducing pore space, hindering water infiltration, and suffocating soil life.

- Pollution: Chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and industrial runoff contaminate soil, harming beneficial organisms and disrupting the nutrient balance.

Positive Influences

- Intentional Additions: Composting and adding organic amendments build soil fertility, improve structure, and boost biological activity.

- Conservation Practices: No-till farming, cover cropping, and terracing all preserve topsoil and foster healthy soil formation processes.

The balance of positive and negative human impacts ultimately determines whether we degrade or enhance soil resources for future generations. Understanding the complexity of the soil formation process is vital for sustainable land management that maintains this precious foundation of life.

Conclusion:

The soil formation process is a testament to nature’s remarkable capacity for transformation. What begins as barren rock evolves into a complex, life-sustaining ecosystem. Soil is far more than just dirt beneath our feet.

The soil formation process is an ongoing journey, shaped by time, climate, and both natural and human influences. Understanding this process highlights the urgent need to protect our soil resources. Sustainable practices like reducing tillage, promoting biodiversity, and preventing erosion will help ensure that our soils can continue supporting life on Earth for future generations.