Introduction: Fire and Ice on the Red Planet

Could the same eruptions that once cloaked Mars in fiery dust also have buried frozen water beneath its equator?

Recent studies suggest that explosive volcanism on Mars might have injected massive amounts of water vapor into the thin Martian atmosphere, which then condensed and fell back as ice, trapped under thick volcanic ash for billions of years.

NASA’s orbiters have spotted traces of hydrogen—possible signatures of ice—in places where ice shouldn’t survive: near the Martian equator. A 2025 Nature Communications study adds to this mystery, proposing that ancient volcanic eruptions on Mars deposited up to 16 feet (5 meters) of ice with each event.

This revelation doesn’t just change how we picture Mars’ past—it may redefine where humans can find water in the future.

Read Also: Living on Mars: The Shocking Truth About How Close We Are to Making It a Reality in 2025

Understanding Explosive Volcanism on Mars

What Is Explosive Volcanism?

When magma rich in gas and water meets sudden decompression, it doesn’t just ooze—it explodes. This phenomenon, known as explosive volcanism, creates towering plumes, spreading ash and fine particles across vast landscapes.

Unlike the slow lava flows of Hawaii, explosive eruption events on Mars were violent enough to eject material hundreds of miles into the air.

Why It Matters on Mars

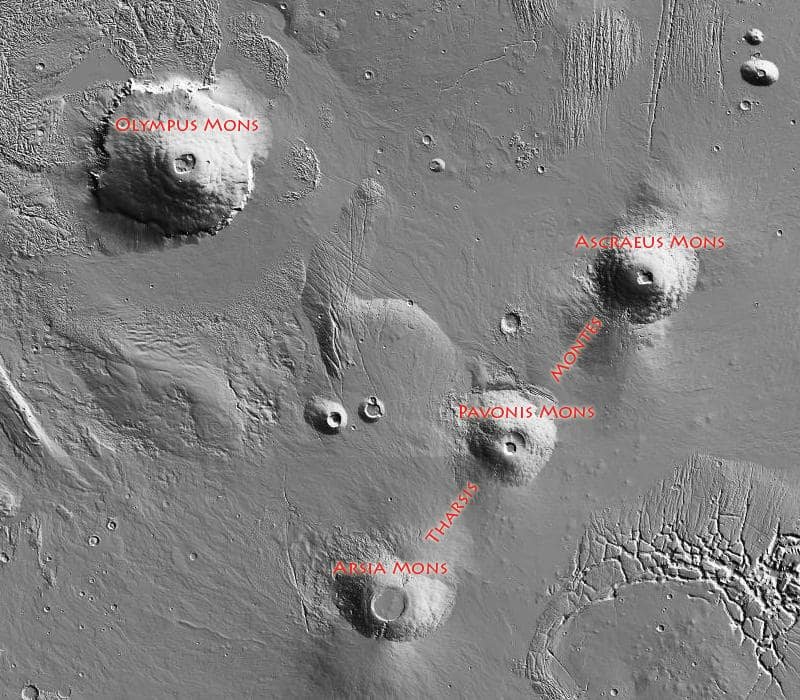

Mars’ lower gravity and thin atmosphere once led scientists to believe that its eruptions were mostly gentle, effusive ones. However, geological evidence from regions like the Tharsis volcanic province now points to a long history of intense, explosive activity.

These findings suggest Mars may have been far more geologically dynamic—and wetter—than we once imagined.

Mars’ Volcanic Legacy: A Quick Overview

| Volcanic Region | Type of Activity | Approx. Age (Billion Years) | Notable Features |

| Tharsis Province | Shield + Explosive | 3.8 – 0.5 | Olympus Mons, Ascraeus Mons |

| Elysium Planitia | Basaltic + Pyroclastic | 3.2 – 0.1 | Cerberus Fossae lava flows |

| Medusae Fossae Formation | Explosive Ash Deposits | 3.5 – 1.0 | Thick ash layers, radar-detected ice |

| Arabia Terra | Explosive Caldera Systems | 4.0 – 3.0 | Mega-calderas, volcanic sediment evidence |

Each of these regions contains ash layers and structures consistent with explosive volcanism on Mars, implying that the Red Planet experienced recurrent eruptions for nearly half its geological life.

Read Also: 7 Largest and Most Dangerous Volcanoes by Continent You Should Fear

The Ice Mystery: Equatorial Ice on Mars

A Paradox of Place

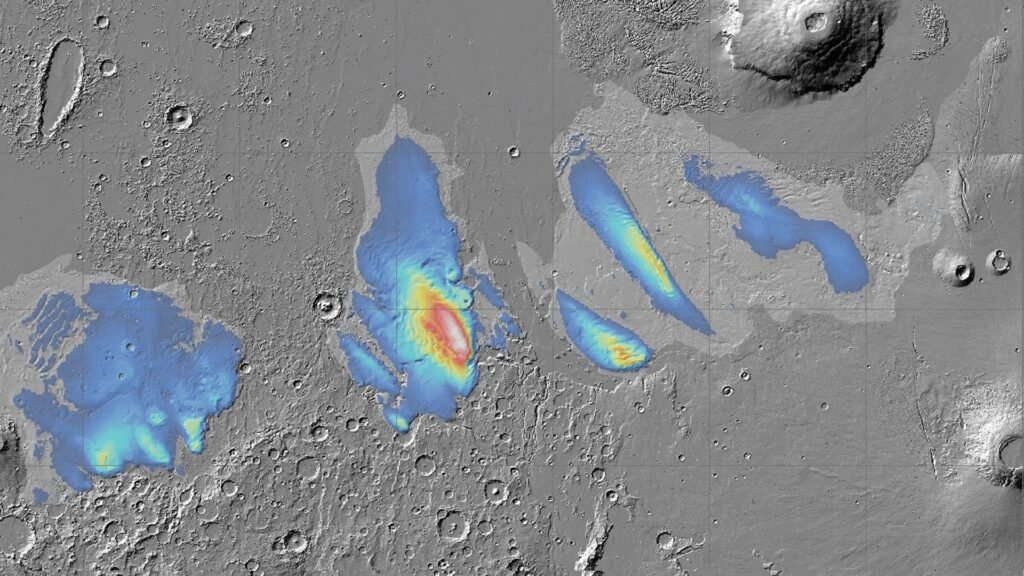

On Earth, ice accumulates at the poles. Mars should be the same—yet orbiters like NASA’s Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have detected hydrogen anomalies near its equator.

These signals likely point to equatorial ice on Mars, locked beneath volcanic debris.

How Could Ice Survive There?

It’s all about insulation. When an explosive eruption occurs, ash and volcanic rock bury the ground beneath. If ice forms underneath that debris, it’s shielded from sunlight and sublimation.

This protective blanket could have preserved equatorial ice for billions of years, hidden from view but detectable by modern instruments.

How Explosive Volcanism on Mars Created Ice

One of the most fascinating outcomes of recent planetary studies is the discovery that explosive volcanism on Mars may have directly contributed to the creation of ice at the planet’s equator. Research led by Dr. Saira Hamid from the University of Arizona presents a compelling model showing how repeated volcanic eruptions on Mars, occurring between 4.1 and 3 billion years ago, may have injected staggering amounts of water vapor into the thin Martian atmosphere. These events, though transient—often lasting just three days—had planetary-scale consequences.

During those eruptions, the interaction of magma with subsurface ice or hydrated minerals released large volumes of water and gases such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide. In the rarefied Martian air, the vapor rapidly cooled, rising into the upper atmosphere before condensing into ice crystals. These fine crystals then drifted downward, coating the Martian surface—especially at the equatorial regions, where prevailing atmospheric circulation patterns carried moisture from the Tharsis volcanic province toward lower latitudes.

Read Also: Explosive Threat: Top 10 Most Dangerous Volcanoes on Earth

According to Hamid’s simulations, each explosive eruption could have produced enough water vapor to create an ice layer up to 5 meters (16 feet) thick over vast areas. Given that explosive volcanism on Mars was not a one-time phenomenon but repeated hundreds—possibly thousands—of times, the cumulative buildup could easily have formed equatorial ice on Mars tens of meters thick. The presence of thick volcanic ash layers over this ice likely provided insulation, preventing sublimation and allowing the ice to remain stable for billions of years.

This cycle of fire producing ice might also explain why modern orbiters—such as NASA’s Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter—have detected hydrogen anomalies near the equator, suggesting hidden ice deposits. Furthermore, these eruptions may have triggered a short-term volcanic winter on Mars, when the cooling effects of ash and aerosols helped preserve the newly formed ice.

In essence, explosive volcanism on Mars acted as a natural climate engine—warming the atmosphere briefly through eruption heat, then cooling it long-term as volcanic gases reflected sunlight. This dual effect not only reshaped Mars’ surface but also left behind an enduring signature: frozen water born from fire.

The Climatic Chain Reaction: Volcanic Winter on Mars

Explosive volcanism on Mars didn’t just sculpt the surface—it may have rewritten the planet’s entire climate history. Just as Earth once suffered “the year without a summer” after Mount Tambora erupted in 1815, volcanic eruptions on Mars could have produced similar large-scale cooling episodes. These frigid intervals, often described as a volcanic winter on Mars, may have been key to the formation and preservation of equatorial ice.

Mechanism of Cooling

During intense explosive volcanism on Mars, massive quantities of sulphur dioxide (SO₂), ash, and fine dust were blasted high into the thin Martian atmosphere. Despite Mars’ lower atmospheric density—less than 1% of Earth’s—the sheer scale of these eruptions made them planet-altering events. Researchers estimate that a single explosive eruption could have released up to 100 million tons of volcanic gases, forming a hazy veil that circled the planet within days.

These aerosols and ash particles acted like mirrors, reflecting sunlight into space. As global solar input dropped, surface temperatures may have fallen by 5–10°C (9–18°F)—enough to initiate a prolonged cooling phase. The result: a temporary volcanic winter on Mars that likely lasted for decades after each eruption. Such chilling events would have slowed the sublimation of surface frost and allowed equatorial ice on Mars to form and persist, particularly when combined with ash layers that trapped moisture below.

Read Also: Land of Contradiction – Why is Iceland volcanically so active?

The team led by Dr. Saira Hamid modeled this process in detail, showing that repeated cycles of explosive volcanism on Mars between 4.1 and 3.0 billion years ago could have drastically altered the planet’s water cycle. Each eruption added new layers of ash and ice, gradually building a subsurface reservoir of frozen water—especially near the Tharsis volcanic province, where volcanic activity was most intense.

“Each major eruption could have lowered global temperatures by several degrees, making it easier for water ice to stabilize,” the study notes.

Over millions of years, this pattern repeated countless times. While Mars burned with volcanic fury above, it quietly froze beneath—turning fire into ice and chaos into preservation. Today’s buried equatorial deposits may be the silent record of that ancient, chilling dance between eruption and frost.

Read Also: Volcanoes – The Science And Secrets Of The Mountains Of Fire

Geological and Astrobiological Implications

The intersection of volcanic heat and frozen water makes Mars one of the most scientifically fascinating worlds in our solar system. The story of explosive volcanism on Mars isn’t just about planetary geology—it’s also about the potential for life. Each eruption reshaped the planet’s crust, atmosphere, and possibly, its biological possibilities.

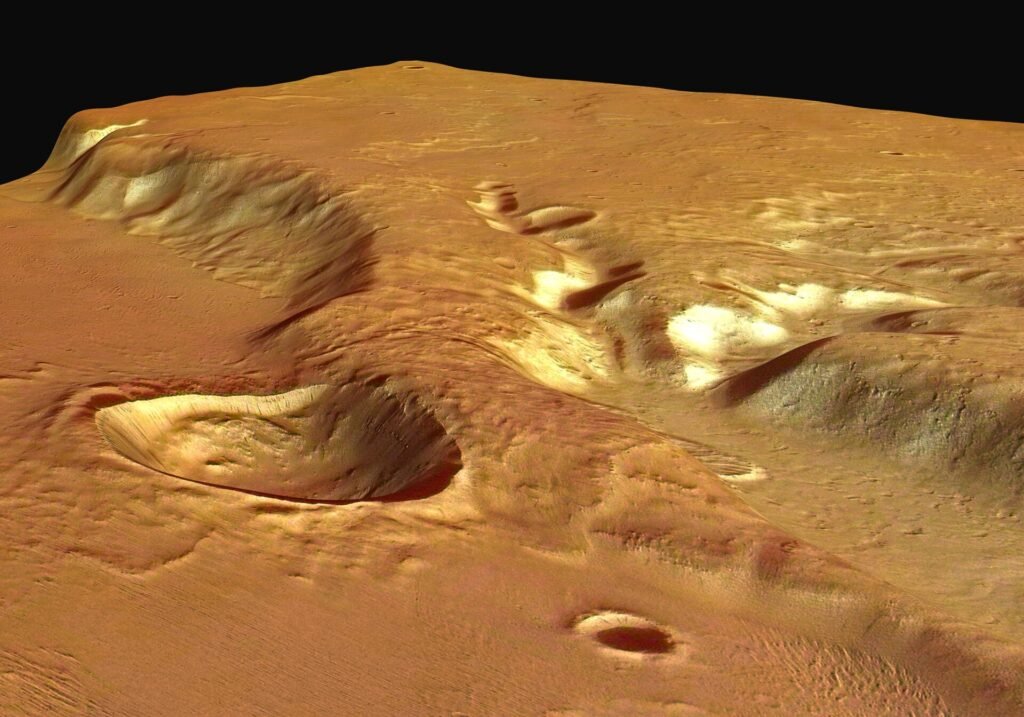

1. Hydrothermal Systems: When Fire Met Ice

One of the most compelling consequences of explosive volcanism on Mars is the likely formation of hydrothermal systems. When hot magma intruded into subsurface layers rich in permafrost or buried ice, the contact generated enormous heat exchange—melting frozen ground and producing liquid water.

According to planetary models, such reactions could have created hydrothermal vents with temperatures between 150–250°C (300–480°F). These vents may have persisted for thousands of years, sustaining localized ecosystems similar to those around volcanic ridges on Earth’s ocean floor.

The Tharsis volcanic province, the epicenter of ancient volcanic eruptions on Mars, is a prime candidate for such systems. Here, repeated explosive eruptions could have melted equatorial ice, driving the flow of mineral-rich fluids through porous basalt.

This process might have produced minerals like silica, serpentine, and sulfates—all known to form in water-rock interactions, and all detectable by NASA’s orbiters and rovers today.

In geological terms, explosive volcanism didn’t just change the terrain—it temporarily brought Mars to life.

Read Also: Why Are the Oceans Blue? The 3 Secrets Behind the Color of the Sea

2. Volcanic Minerals and Biosignature Preservation

When explosive volcanism on Mars expelled ash, gases, and molten rock, it also generated ideal conditions for the preservation of biosignatures—chemical or structural traces of life.

Volcanic minerals such as opaline silica, hematite, and clay minerals can entomb microorganisms or organic compounds rapidly, shielding them from radiation. Data from the Spirit and Curiosity rovers show these minerals concentrated in past hydrothermal regions, hinting that ancient microbes—if they existed—might have been trapped there.

In comparison to Earth, where volcanic ash preserves microfossils for millions of years, Mars’ dry, cold environment would have slowed decay even further. Thus, regions affected by explosive volcanism—especially the Tharsis volcanic province and the Medusae Fossae Formation—stand as prime hunting grounds for fossilized biosignatures.

Furthermore, the overlap of volcanic winter on Mars periods and water-rich eruptions could have promoted cycles of freezing and thawing, another key mechanism for organic preservation.

Read Also: Types of Volcanoes: A Guide to the 6 Most Dangerous Forms

3. Equatorial Ice: A Hidden Resource and a Scientific Beacon

The discovery of equatorial ice on Mars beneath volcanic ash layers revolutionizes our view of habitability. Traditionally, scientists believed ice could only persist near the poles due to lower temperatures. Yet, modeling studies show that explosive volcanism on Mars may have buried large ice sheets under insulating debris.

Each explosive eruption may have deposited up to 5 meters (16 feet) of ice, quickly covered by ash that prevented sublimation. This means water—essential for life—could have remained stable even near the sun-baked equator.

For future explorers, these ice deposits hold immense promise. They represent not only geological evidence of the planet’s active past but also potential water sources for human missions. NASA’s ongoing radar mapping of the Tharsis volcanic province and surrounding equatorial plains aims to locate and confirm these hidden ice layers.

Where there was fire, there may still be frozen water—and where water lingers, the story of life may still be written.

4. A Planet Momentarily Habitable

In conclusion, explosive volcanism on Mars did far more than sculpt its red deserts. By uniting magma and ice, it forged temporary oases of heat, moisture, and chemical energy—the same ingredients that sustain microbial ecosystems on Earth.

For a brief epoch in Martian history, volcanic eruptions on Mars may have turned a barren landscape into a world with warm springs, flowing water, and minerals capable of preserving life’s faintest signatures.

Read Also: Detecting Life on Mars: A Breakthrough in Space Research

Key takeaway:

The evidence from the Tharsis region and equatorial plains suggests that Mars’ explosive volcanism didn’t just shape the surface—it created fleeting windows of habitability, locking the planet’s biological potential beneath its volcanic scars.

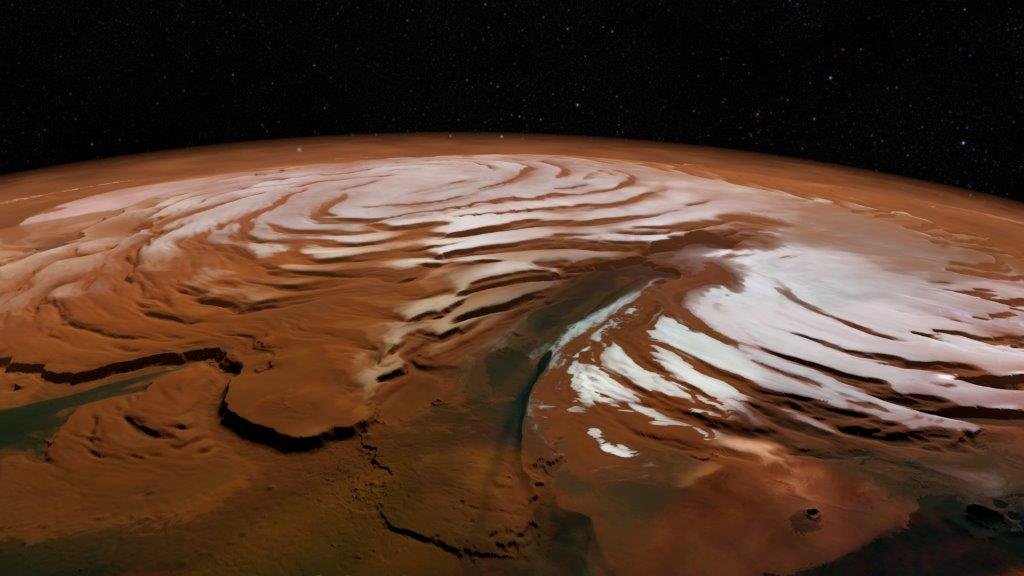

The Tharsis Volcanic Province: The Heart of Martian Fire

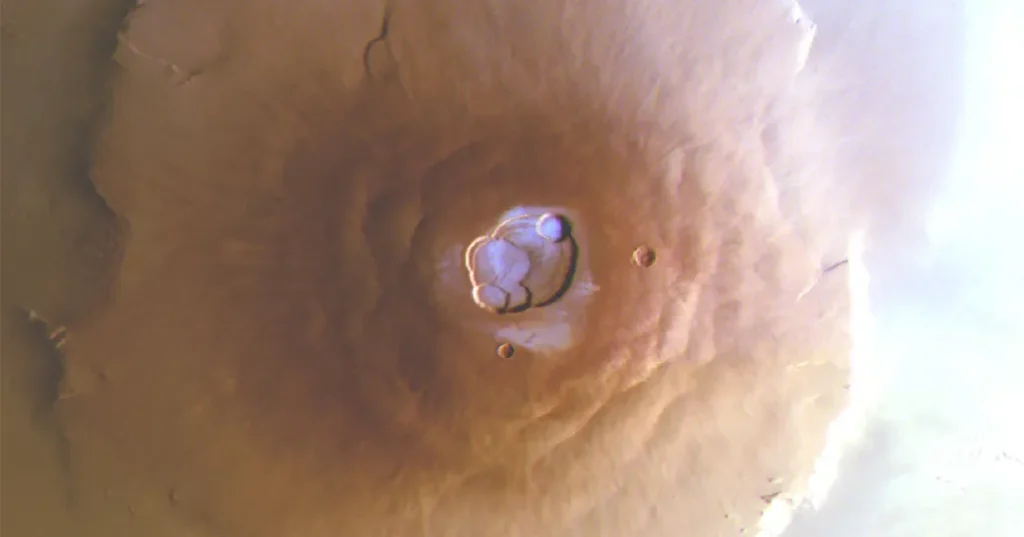

The Tharsis volcanic province is home to the largest volcanoes in the solar system, including Olympus Mons.

But beneath its colossal lava flows lie deposits hinting at pyroclastic (explosive) activity.

Researchers now believe that these eruptions launched ash and water vapor into the global circulation, depositing ice even far away in equatorial regions.

This vast volcanic plateau might have been the main contributor to the global redistribution of ice during Mars’ explosive era.

Table: Comparing Explosive Volcanism—Earth vs. Mars

| Feature | Earth | Mars |

| Gravity | Strong | Weak (38% of Earth’s) |

| Atmosphere | Dense | Thin (mostly CO₂) |

| Eruption Column Height | 20–40 km | Up to 80 km |

| Primary Volcanic Gas | H₂O, SO₂ | CO₂, H₂O, SO₂ |

| Ice Deposition | Rare (local) | Equatorial possible |

| Cooling Duration | Years | Centuries (estimated) |

Mars’ weaker gravity allows eruption plumes to reach far greater heights, spreading ash and water vapor globally—key to forming and burying equatorial ice.

Read Also: Volcanic Eruption Prediction in 2025: 5 Proven Methods for Accurate Forecasting

What These Findings Mean for Future Missions

Equatorial Ice: A Game-Changer for Human Exploration

The discovery of explosive volcanism on Mars and its connection to equatorial ice on Mars isn’t just scientific—it’s strategic. Equatorial regions receive steady sunlight, ideal for solar power, and offer gentler landing conditions compared to the poles. If subsurface ice exists beneath volcanic ash, as models suggest, it could transform mission logistics.

According to the 2025 Nature Communications study, ice layers up to 16 feet (5 meters) thick may lie buried beneath ancient volcanic deposits. For astronauts, this means potential access to water within reach of equatorial bases—no need to transport heavy reserves from Earth or traverse to the icy poles.

Technology to Confirm the Hidden Ice

Future robotic explorers will play a crucial role in confirming this theory.

- NASA’s Mars Sample Return and ESA’s ExoMars missions are equipped with advanced instruments capable of detecting subsurface materials.

- Future rovers may use ground-penetrating radar and neutron spectrometers can confirm hidden ice layers beneath volcanic ash and differentiate them from hydrated minerals—vital in verifying the effects of explosive eruption events that shaped Mars.

If verified, the deposits left by explosive volcanism on Mars could become humanity’s first extraterrestrial water wells.

Read Also: Breaking News: Is Alaska’s Mount Spurr About to Blow?

Key Takeaway

Explosive volcanism on Mars wasn’t just about fire and ash—it was also about ice and climate. The same eruptions that scorched the surface may have secretly preserved water at the planet’s equator, rewriting what we know about Martian history and habitability.

Conclusion: Mars—A Planet of Paradox

The story of explosive volcanism on Mars blends extremes—heat and cold, destruction and preservation.

Ancient eruptions transformed Mars’ thin skies into fleeting storms of ice, leaving their frozen legacy buried under volcanic plains.

For scientists, this revelation deepens our understanding of how planets evolve and how fire can give birth to water in the unlikeliest of places.

As we prepare for human exploration, these equatorial ice deposits—born of catastrophic volcanic eruptions on Mars—could become the lifeblood of future settlements.

In the union of volcano and ice, Mars still whispers its secrets: a frozen past forged in fire.

FAQs

1. What caused explosive volcanism on Mars?

Volatile-rich magma and rapid decompression triggered massive eruptions, spreading ash and water vapor across Mars’ atmosphere.

2. How do we know there’s ice near the Martian equator?

Orbiters detected hydrogen signatures—strong indicators of buried water ice beneath ash in equatorial regions.

3. Did these eruptions make Mars temporarily habitable?

Possibly. Volcanic heat and water vapor might have created transient warm zones where microbial life could survive.

4. Why is equatorial ice important for future missions?

It provides potential water sources near optimal landing zones, reducing costs and logistical challenges for human explorers.

5. Could explosive volcanism still occur on Mars today?

Some evidence from the Elysium Planitia region suggests volcanic activity may have occurred within the past 50,000 years—geologically recent.